In the introduction to the book Kono shota ga sugoi (このショタがすごい!) from 1997, Shindōji Gun (真道寺軍) opens with this provocative question:

What are little boys made of?

Kono shota ga sugoi, p. 4

The question evokes so many thoughts. At first, I think about the boy’s body. Like the rest of us, boys are made up of flesh and blood, bones and organs. But just by spelling this out, I realise what a bad answer it is. Of course boys are made of the stuff that makes all of us. Disgusting stuff that I don’t want to see. So why is the boy so great (or “sugoi”) when he’s made of the same things as the rest of us? Is it the composition of these things – the proportions in which the bones are held together? Is it the youthful lustre of the thin layer of skin that so perfectly wraps around the stuff we don’t want to see? Being so concrete about the answer makes me realise that what the question really asks is this:

What is the magic of boys?

That question has been asked before in shota research. In 1996, Manda Ringo phrased it like this in the shota survey published in her book The Syotaroh:

Where does the magic of the boy reside?”

The Syotaroh, p. 15

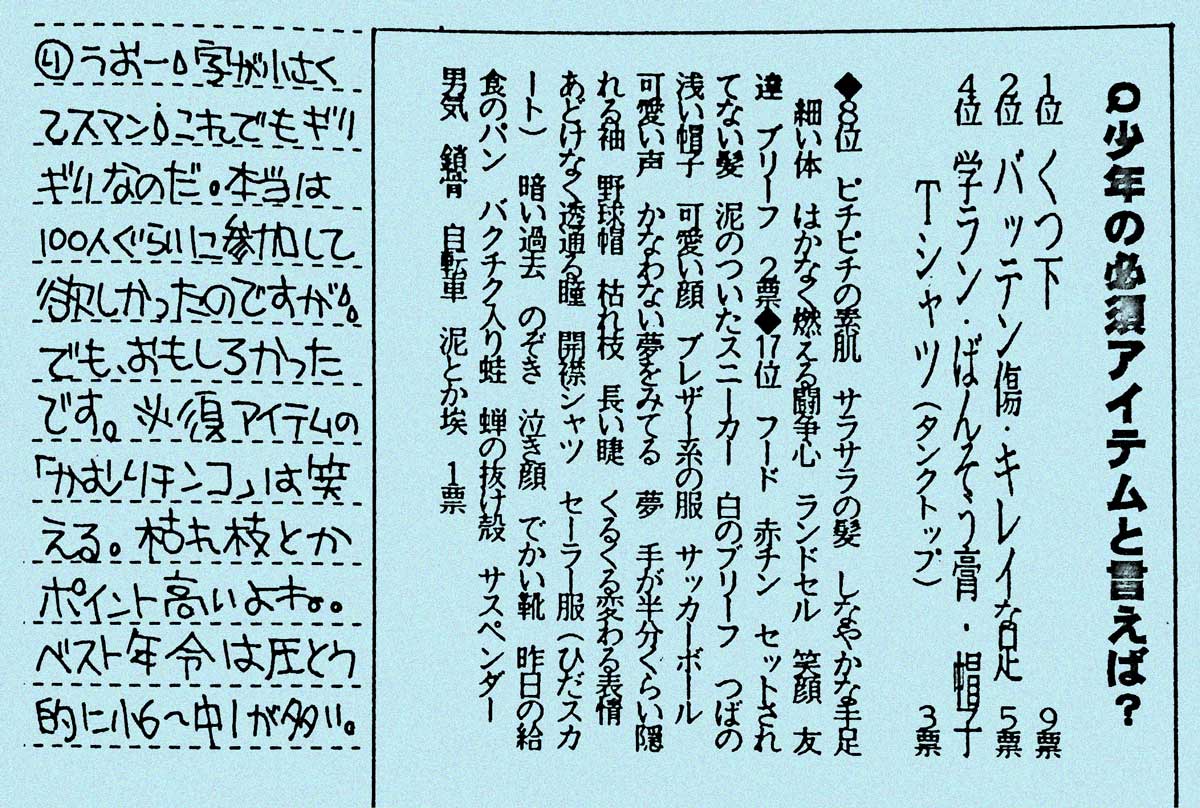

Popular answers included “smooth legs”, “thin limbs”, “beautiful face”, and “youthful skin”, but the number one answer, as entered independently by 13 respondents, was junsuisa (純粋さ), which can be translated as “purity” or “innocence”. This is something far more abstract than the physical attributes. It is something that is hard or maybe even impossible to grasp, and thus it is denoted as “magic”. But maybe one can try by way of examples. The introduction in Kono shota ga sugoi follows an illustration where the same question is posed – twice for impact:

Boys, what are they made of?

Kono shota ga sugoi, p. 3

Boys, what are they made of?

Ray guns and spacecrafts,

what’s more, robot monsters,

What a wonderful anything goes!

The text reads like a poem, and maybe poetry is the only way one can close in on questions about magic.

The continuous outpour of books and dōjinshi discussing shota reflects a will among shota fans to understand themselves. Like few other genres, shota seems to create a curious reflexivity among its readers, who are more diverse than readers of other comics. Women and men, young and old, straight, gay and bi, ask themselves: What is the magic of the boy?

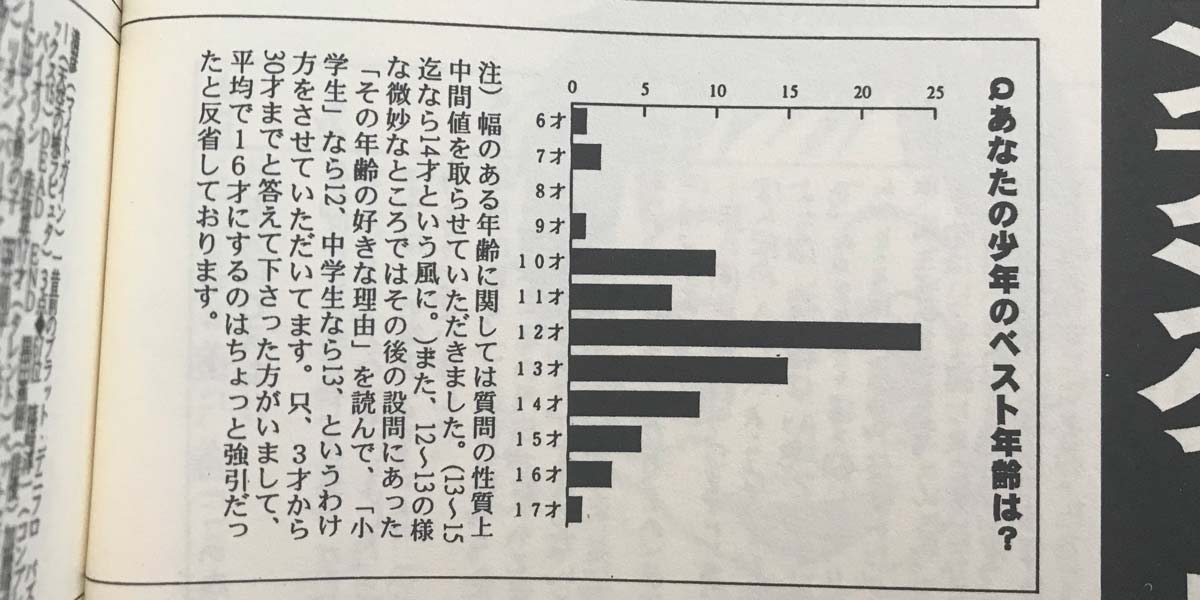

In academic terminology, one might talk about the ontology of the boy, as a way to try to capture his very being. The passionate production of shota dōjinshi provides a unique chance to close in on this transient ontology called Boy: How old is he? (Twelve!) What does he look like? What hobbies does he have? Of course there are many answers depending on personal taste, but taken together, the expressions in these dōjinshi make up an important databank devoted to an ideal that never lets itself be captured, and which therefore keeps engaging us.

So I ask you: What is the magic of the boy? Reply in the comments or in the shota forum – and don’t forget to take the shota survey!