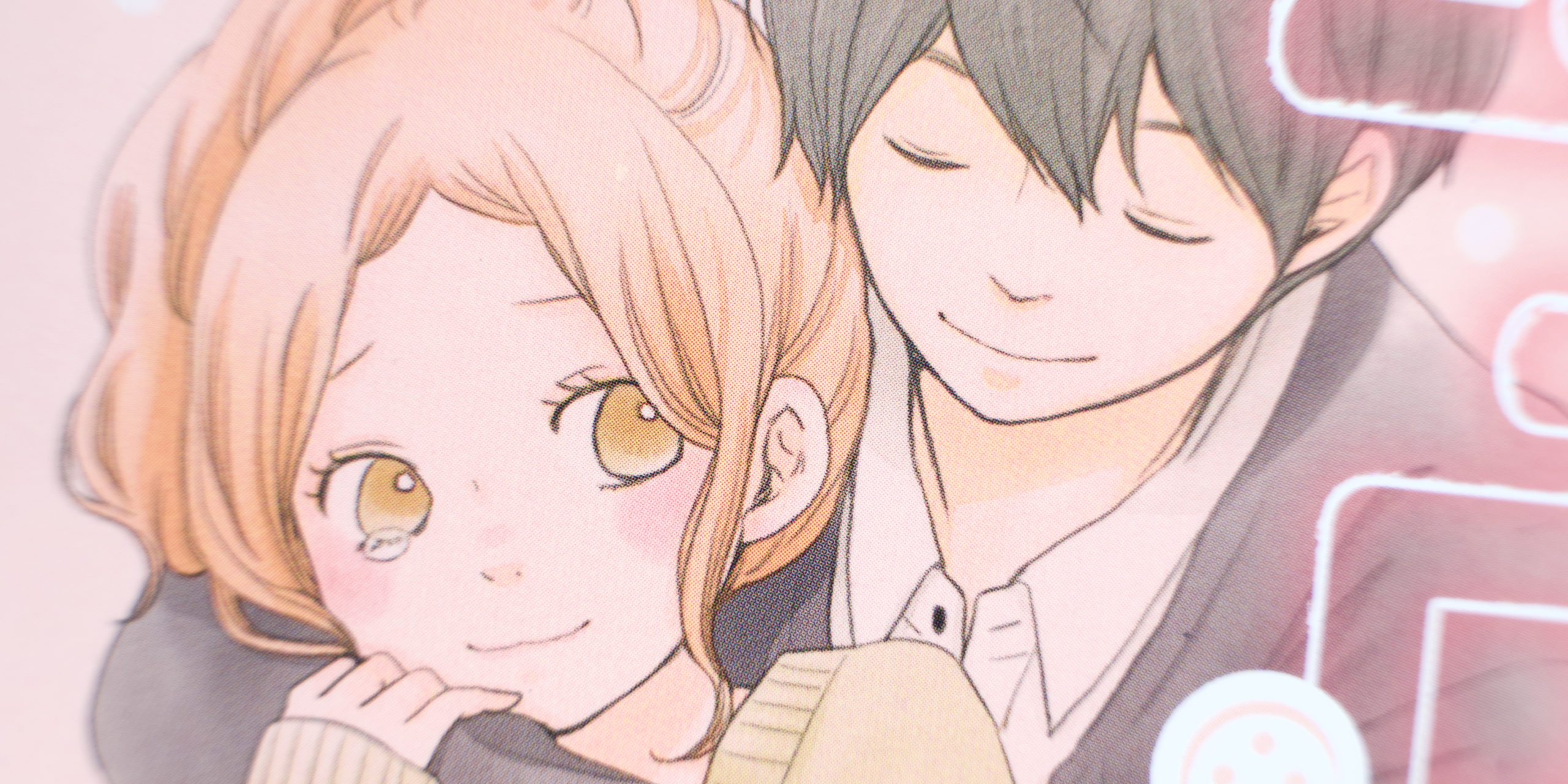

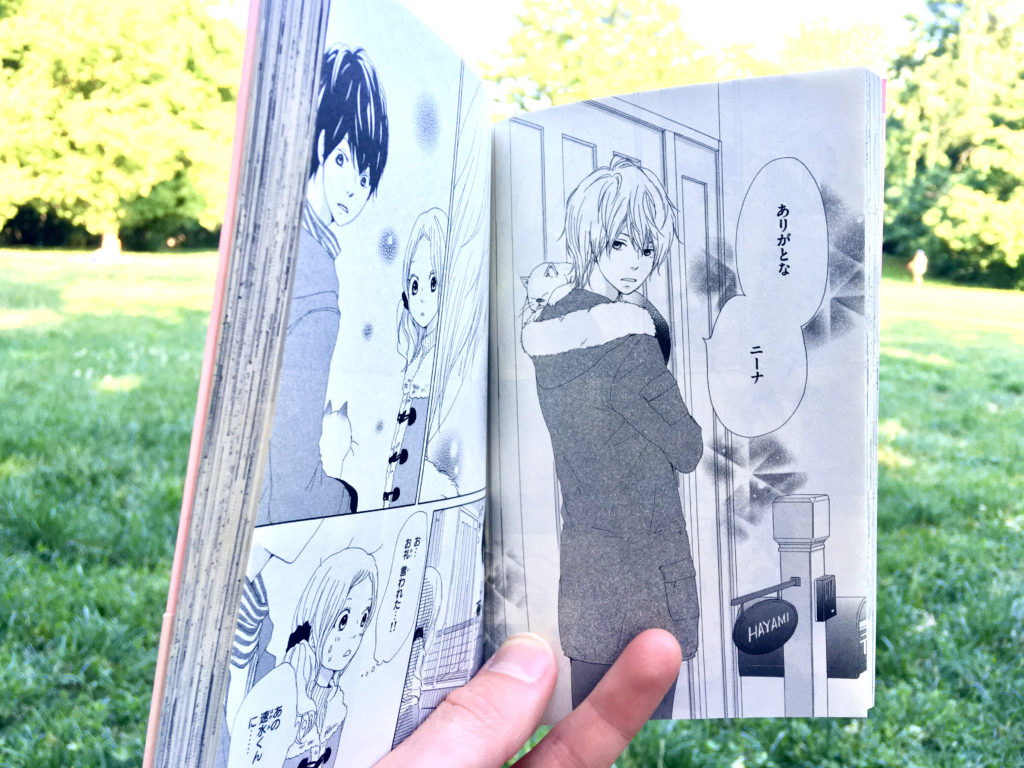

Kasuga Nīna is the protagonist of Usami Maki-sensei’s shōjo manga Kokoro Button. She’s dating Kōga Eito. In chapter 25, in tankōbon volume 6 from 2011, Kasuga-san has helped Kōga-kun’s friend Hayami Manabu to find his lost cat. The chapter ends with Hayami-kun thanking Kasuga-san with the words:

Thanks, Nīna

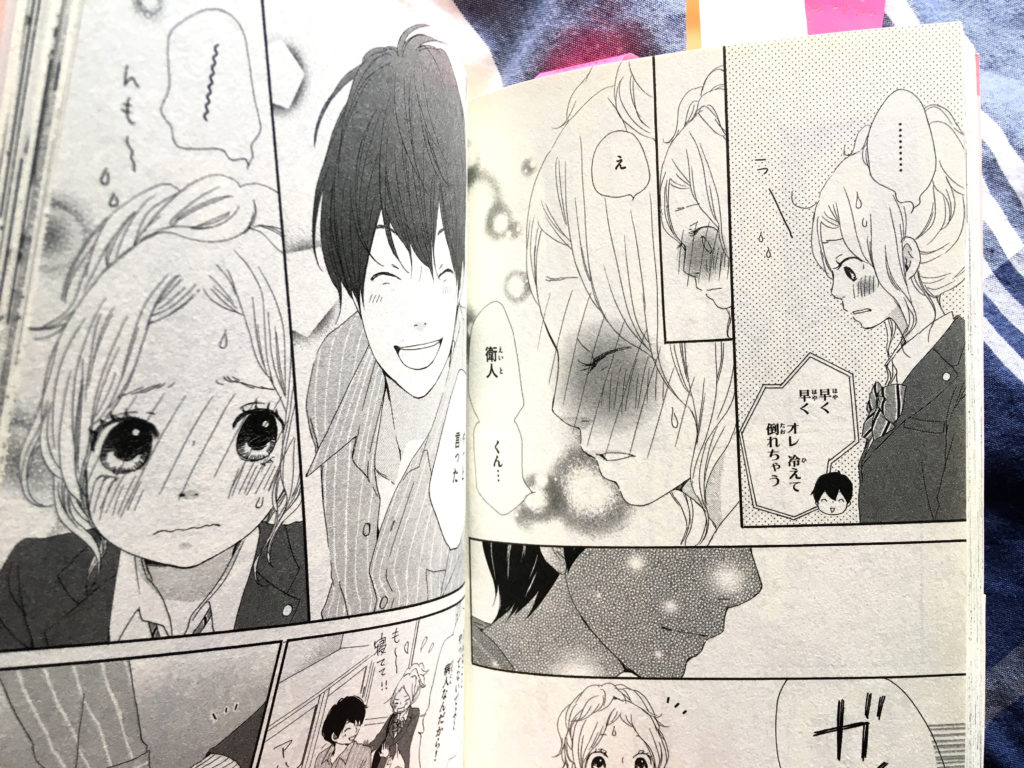

Kokoro Button, vol. 6, p. 78

ありがとな ニーナ

The impact of this phrase shakes the protagonist and her date to the extent that it will dominate the whole next chapter.

Crash course in Japanese name suffixes

To understand why, we must dive into the subtle art of how names are used in Japan to signal distance or intimacy:

- The suffix -san is the neutral form that anyone can use, as in Kasuga-san.

- The suffix -kun is used for boys and younger men, but also for male subordinates. It implies a somewhat affectionate relation.

- The suffix -chan is used for girls and younger women in an affectionate way.

- If the suffix is added to the first name, it’s more intimate than when it’s added to the family name.

- The most intimate thing of all is first name and no suffix at all!

This is just a rough overview, the complexities of how suffixes are used, and by whom, is a subject in itself that you will have to read up on elsewhere. Suffice it to say that when Hayami-kun both drops the suffix and calls Kasuga-san by her first name it signals an intimacy that threatens the relationship between Kasuga-san and Kōga-kun, as if Hayami-kun had “had” Kasuga-san!

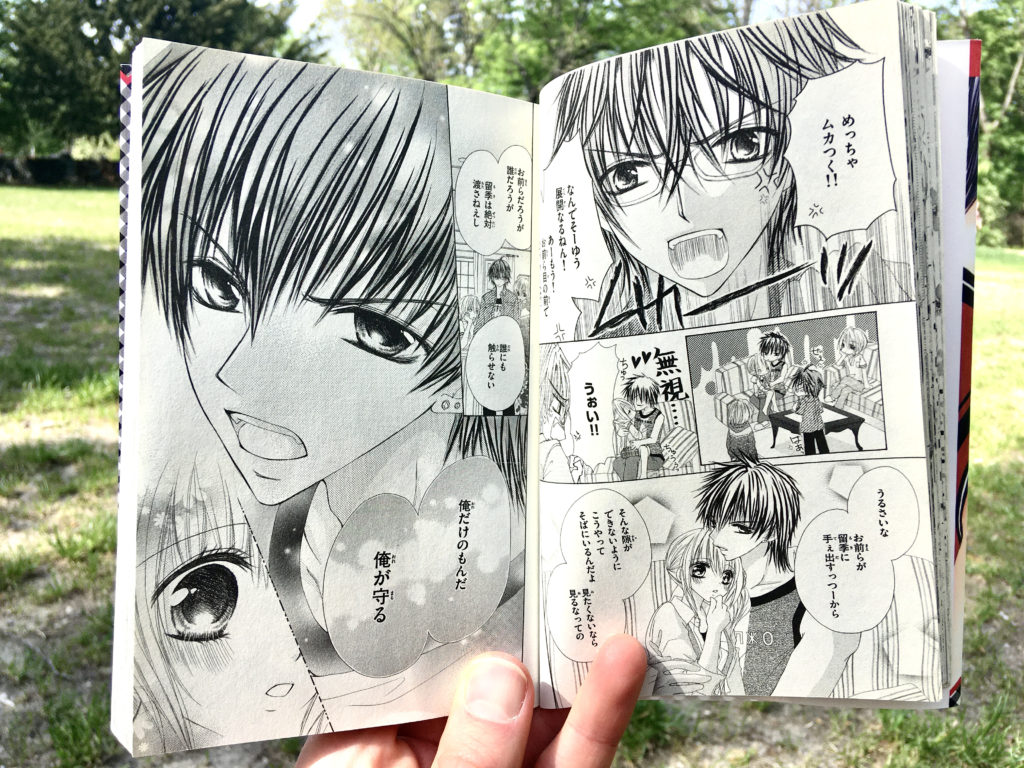

It’s telling that Kasuga-san’s and Kōga-kun’s stunned reaction is the very last frame of the chapter, Kōga-kun looking at his girlfriend, maybe both questioning her and accusing her. This is a cliffhanger supreme for a series that was originally published in the monthly magazine Betsucomi.

My own experiences

I once experienced how a person allowed me to drop the -kun after we had slept together. Continuing calling someone -kun after you’ve had sex would be as ridiculous as referring to them as “Mr”. (So I was politely scolded for doing so.)

I also once experienced with a group of Japanese friends at a bar how one man referred to a woman, sitting next to him, with her first name, no suffix. My closest Japanese friend leaned over to me and explained: “When he calls her by her first name like that, the rest of us know that they are an item.”

The same friend also told me that as a grown-up he didn’t expect to meet another man ever, for the rest of his life, with whom he would drop the suffix; that honour is reserved for the friends you grew up and went to school with.

First name drama

Back to Kokoro Button: In the next chapter, Kasuga-san receives the news that her female classmate has started to be on a first name basis with her boyfriend. Kasuga-san is clearly envious, and when she meets Kōga-kun, she tries to call him by his first name, Eito, but fails. Only “e-” and “ei…” come out. The smart boyfriend gets what she’s trying to do though, and teases her: “And then?”

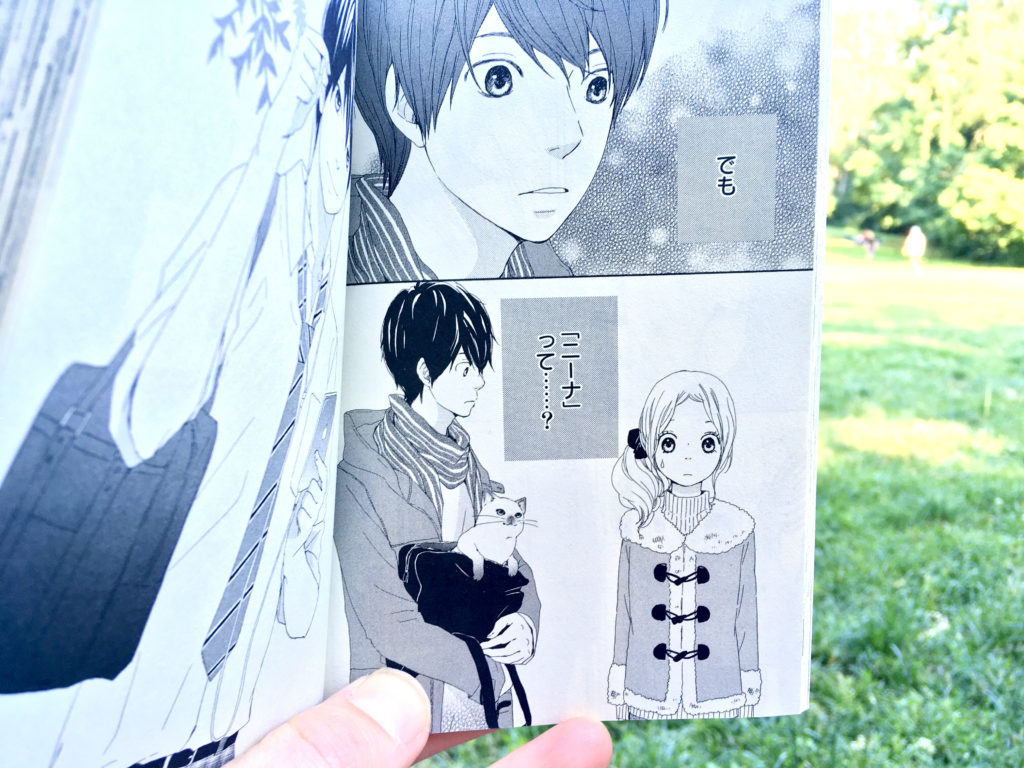

As for Hayami-kun, it turns out – again, at the climactic end of the chapter – that he had mixed up Kasuga Nīna-san’s names – he thought Nīna was her family name! Despite being a bad boy who tells people off the whole time, the fact that he had called his best friend’s girlfriend by her first name torments him endlessly – so grave was the offence!

Although this particular interaction is not followed up upon, I see the fact that Hayami-kun falls in love with Kasuga-san later on in the manga partly as a result of this early trespassing into her intimate sphere. Once there, he was stuck, sort of thing!

The next level of intimacy

Inspired by Kasuga-san’s failed attempts to call him by his first name, Kōga-kun suggests that he, as her boyfriend, starts calling her by her first name. Kasuga-san is in shock. She blushes. But she wants this. We have been primed with the news of her classmate taking this step with her boyfriend, a step almost as serious as a proposal, it seems. And then he says it:

Nīna

Kokoro Button, vol. 6, p. 112

新奈

The power of calling your lover by their first name! As a reader I’m as excited as Kasuga-san, who is thinking to herself:

(Gasp!) Why this sudden feeling … This person only spoke my name … And yet my heart is starting to beat … It’s beating faster and faster …

Kokoro Button, vol. 6, p. 113–114

Kōga-kun laughs as he speaks her name, comments that it’s embarrassing for both of them. And then he implies that it’s her turn. Can she call her boyfriend by his first name, Eito?

As it turns out, no. Again, Kasuga-san is like:

E… Ei… Ei…

Kokoro Button, vol. 6, p. 115

And again, Kōga-kun encourages her: “And then?” But to no avail – she can’t say his first name! “I guess it will take some time”, Kōga-kun comments, and the chapter ends.

Forcing her to speak his name

The next chapter begins with Kasuga-san boasting to her female friends (who all call her Nīna), that Kōga-kun has called her by her first name. They congratulate her and Kasuga-san plays coy. “Oh, it’s nothing really.” But we know that it isn’t nothing!

When Kōga-kun appears, she greets him with an excited “Kōga-kun”. When he replies, he addresses her with “Kasuga-san” again. She is surprised. Wasn’t she “Nīna” with Kōga-kun now?

“Ka… ‘Kasuga-san’?”

Kokoro Button, vol. 6, p. 120

“That’s right. You’re not calling me by my name, right? So I thought I’ll just return to how it was before.”

Oh nooo! Kasuga-san is devastated. Kōga-kun seems amused and in the end teases her by calling her “Nīna”-chan. (He’s an “S”, meaning a “sadist” who likes playing with Kasuga-san’s feelings.)

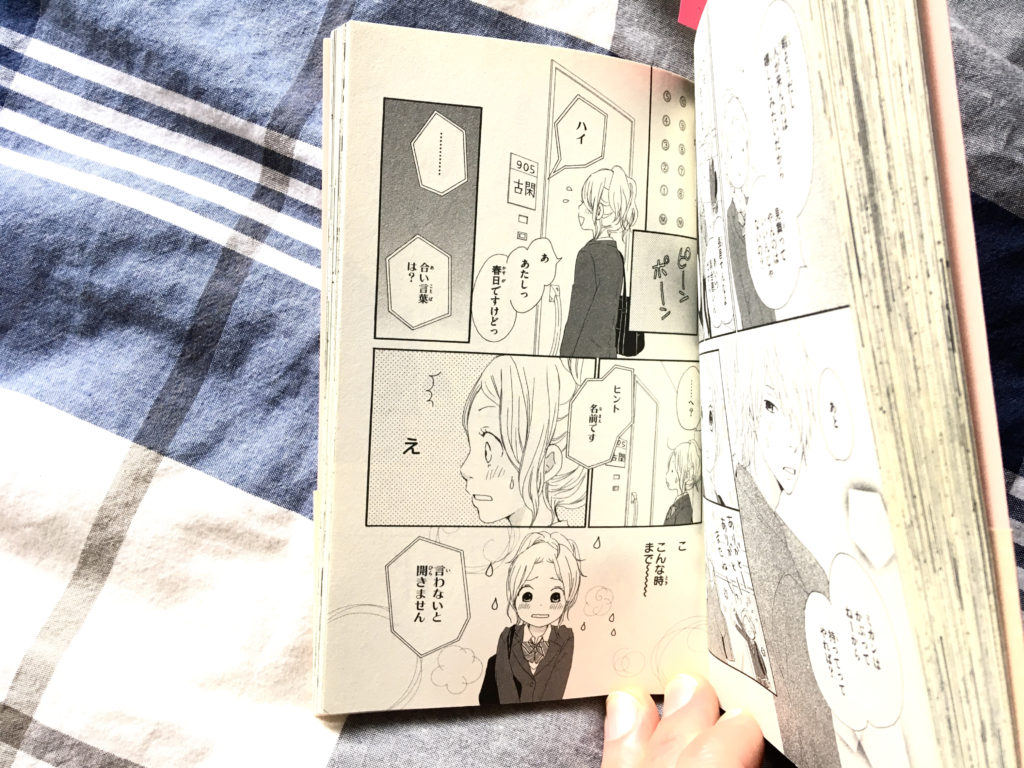

The tension continues throughout the chapter until Kasuga-san is about to visit Kōga-kun, who is home sick. As she calls him from the intercom at the entrance of the house, he replies:

What’s the secret password? I’ll give you a hint: It’s my name. I won’t open until you say it.

Kokoro Button, vol. 6, p. 133

Damn, is this guy cruel or what!

Come on, fast or the fever is gonna make me pass out!

And so Kasuga-san finally says it, in the security of the intercom (not having to face him eye to eye): “Eito” – but she quickly adds a -kun. Well, that’s good enough for now.

The power of transgressions

As the story proceeds, they both go back to calling each other Kōga-kun and Kasuga-san, but the transgression of calling their date by their first name has been made, and it’s an important act of intimacy that will bind them together for the rest of the series.

As an outsider, I’m fascinated by the importance of what you call your partner, and how this dynamic can power story arcs over several chapters, including cliffhangers and resolutions.

Kokoro Button (ココロ・ボタン) by Usami Maki (宇佐美 真紀) was published in Betsucomi between 2009 and 2013, and concurrently in 12 beautiful tankōbon volumes. The series is translated to German and French.