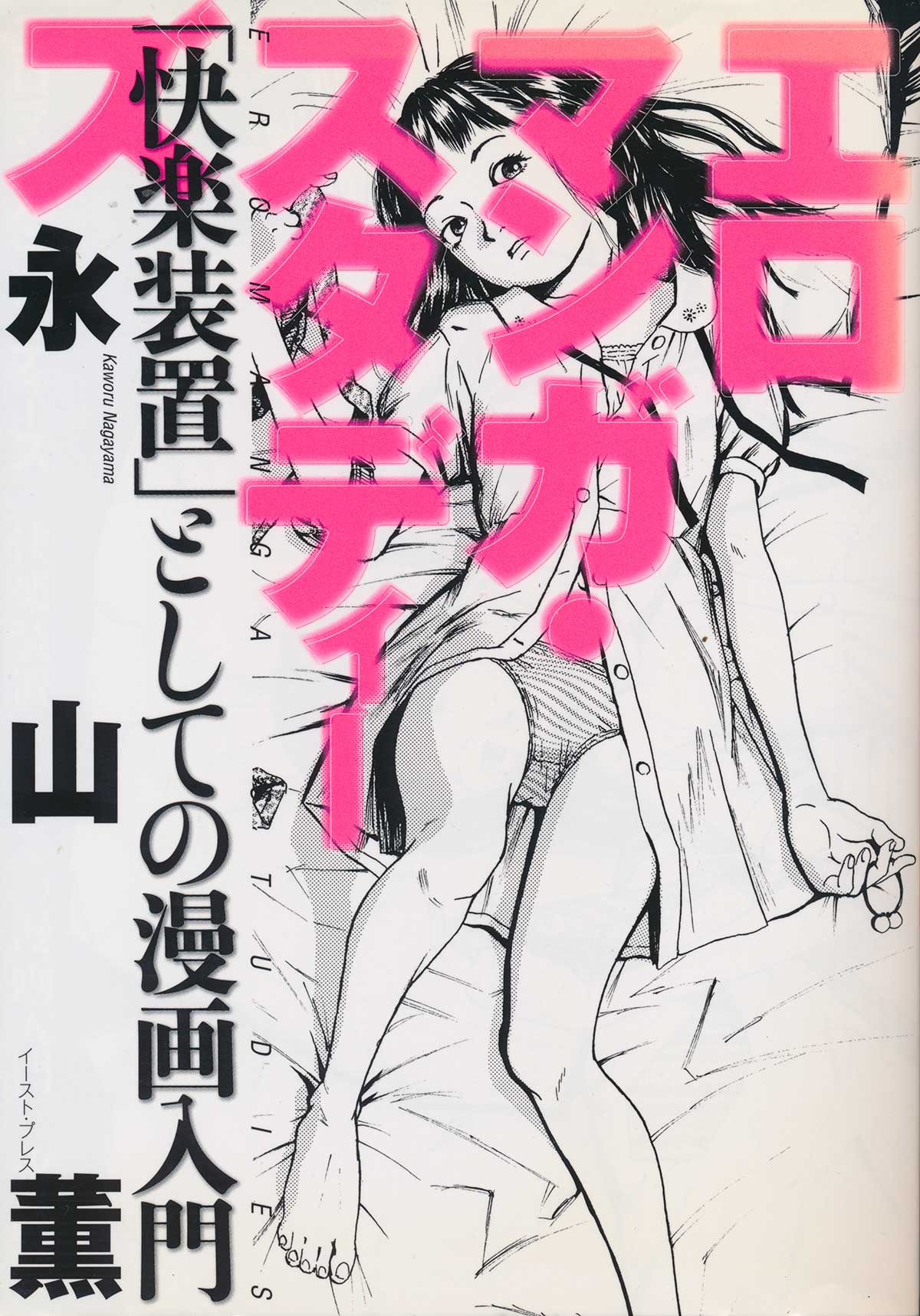

I’ve just finished a close reading of the second shota section of Nagayama Kaoru’s (永山 薫) Eromanga Studies (エロマンガ・スタディーズ) from 2006. While the first section on shota (p. 83-86) covers its history and the boom of female creators in the 1990s, the second section (p. 238-44) analyses the male shota reader by way of some interesting titles. This is a translated summary of those pages.

Background

In the mid 1990s, “male characters as target for desire” in the form of “shota” appeared. In the late 1980s, a dōjinshi critic predicted that “the 1990s will be the era of cute boys”. Although this prediction was delayed due to the bishōjo-eromanga boom in the early 1990s, it turned out to be true.

At first, shota was a subgenre of BL/yaoi. Various factors made it cross the border to become a genre targeted at men. Beyond readers’ and artists’ will to read and draw, there must be a business decision that turns it into a product.

Shota oriented male writers were published in shota anthologies for women. Since it was aimed at women, censoring was not needed. So what was called “for women” on the surface in reality consisted of the three types “purely for women”, “for both sexes”, and “purely for men”. However, this boom stalled in the next decade.

But although male homosexual shota was destroyed, characters that were beautiful boys, neutral-gendered boys, cross-dressing boys, and passive “non-macho boys” spread into the world of erotic manga. Works like Yonekura Kengo’s Pink Sniper (2001) and Hayabusa Shingo’s Sweat & tears (2001) started a mini-boom of “one-shota”, with couplings between a beautiful boy and an older woman. Nagayama sees homophobia as a reason to why shota resorted to the male ╳ female scheme.

In 2002, a small boom occurred with the publication of the shota anthologies “Koushoku-shounen no susume” (2002), “Shounen-ai no bigaku” (2003), and “Shounen shikou” (2003). Shota had thereby been established as a genre, but its future is unknown.

Note: Nagayama-san’s book was published in 2006, so Budōuri Kusuko’s history of commercial shota magazines provides more details in that regard:

Boy on boy shota

Although Nagayama only discusses works aimed at men, he stresses that the coupling is basically boy on boy (少年╳少年) or youth on boy (青年╳少年), but almost never boy on youth (少年╳青年).

And in the case of boy on boy, the seme/uke roles are not always fixed.

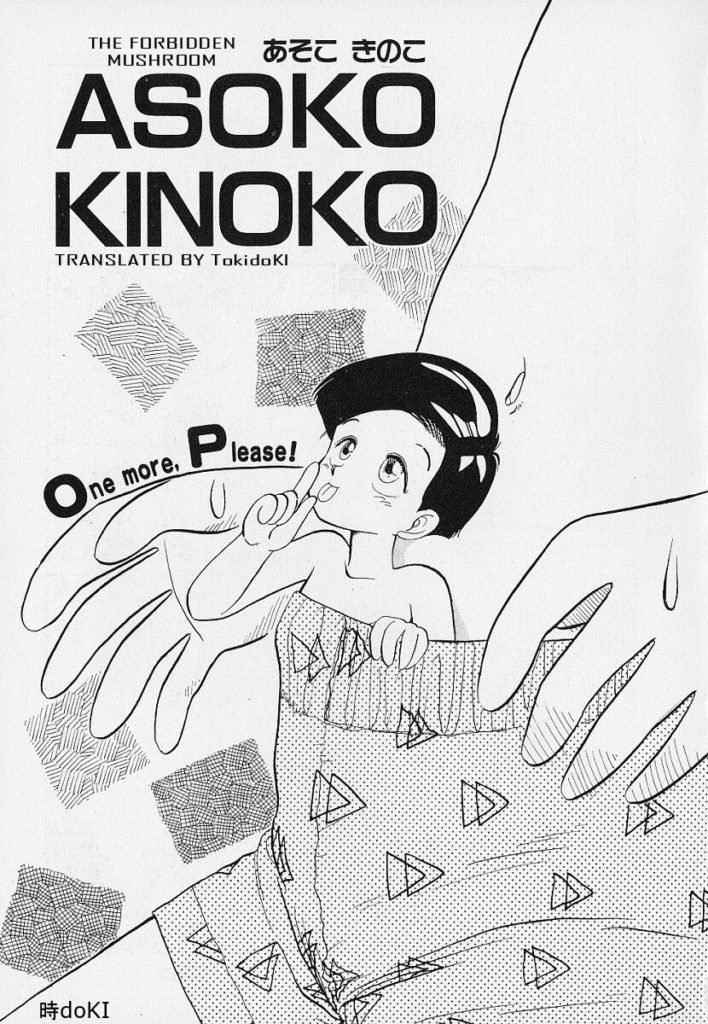

Nagayama provides a hilarious example in the form of Yōkihi’s Asoko Kinoko (1990), in which the penises of two boys are parasitised by autonomous and intelligent mushrooms of feminine forms. These mushrooms live off the boys’ semen as nutrients, and in return provides pleasure to their hosts.

In one scene the boys are kissing deeply while the “mushrooms” in their crotches are having what must be described as lesbian sex. The boys’ seme/uke roles are fluid, sometimes determined by apparent gender difference, height and physique, but only “to some extent”.

Nagayama notes that while the female mushrooms might be titillating for some, as the story progresses they retreat into the background and the boys become the full focus:

It’s a return to a boys only secret society, where sex is the homosocial company secret. Not only is there disdain, fear, and dislike for women, but maybe also fear and dislike for “the outside world”.

Nagayama Kaoru/永山 薫. Eromanga Studies/エロマンガ・スタディーズ (2006), p. 240

Male desire for boys

What kind of desire is it that male readers feel towards boy characters? Nagayama asks. Of course it could be homosexuality, conscious or subconscious. Although some shota reminds of heterosexual ero-manga in that the “uke” in the anal sex a substitute for a woman, the penis sprouting from the boy’s crotch makes it clear that we’re actually dealing with a male delight. The roles are also not that settled and the direction of power might change.

Nagayama notes that all pleasures in shota are physical pleasures. He argues that the reason why latent homosexuals fear gay porn, as represented by Tagame Gengoroh, is not that they don’t understand it, but that they understand the psychological and physical pleasures all too well. “Kawaii” suppresses such homophobia.

In other words, making the boys “cute” is a way to “de-pornify” them, since otherwise the “male pleasure” would be all too evident to the reader, which might evoke uncomfortable questions about his own homosexuality.

In addition, a major premise is that “it’s just a manga character”.

Nagayama identifies various ways in which male readers project their selves on shota characters:

- In the case of youth on boy (青年 ╳ 少年), the gender roles are relatively fixed, which makes it easy for the male reader to project his self on the youth (the heterosexual pattern).

- However, if the story is told from the point of view of the boy, it is easier for male readers to project their selves on an “uke” who is a boy than on an “uke” who is a woman.

- In the case of boy on boy (少年 ╳ 少年), the feeling is the same no matter if you’re “uke” or “seme”.

In the latter case, an illusion is achieved through transformation, as Nagayama has written about in a quoted article:

I transform myself to a cute boy who does sexy things with other cute boys.

Nagayama Kaoru/永山薫: “Sexuality transformation”/セクシュアリティの変容. In Azuma Hiroki/東浩紀, editor: Mōjō genron F aratame/網状言論F改, Seidosha/青土社 collection 3/2003所収.

Nagayama asks rhetorically: Is there really such a big difference between “Cute me = an ideal model of myself” and “Cute you = an ideal model of others”? Even when this ideal model is temporarily entrusted to others, isn’t it always a projection of our self image?

No matter if the “other” that the boy is coupled with is a youth, middle-aged, or old, what we see is ourselves in various generations. In conclusion, shota is about “me and my sex”.

Two illustrative shota works

Tamamimi/たまみみ

Nagayama illustrates the autoerotic structure of shota through Akio Takami’s/秋緒たかみ work “Tamamimi”/たまみみ (in “Juvenile”/じゅぶないる, Shobunkan, 2004):

Terumi was missing his close friend Rōta, and was shocked to have grown cat ears the next morning. According to his grandfather’s reminiscence, if you have feelings for a person you can’t meet, you will grow “soul ears”/魂耳 which listen to that person’s presence. As Rōta too grows soul ears, the two realise that they love each other. The most beautiful thing in this work is the sequence when the soul ears are touched by “the person who thinks about them”, and they realise that it feels good, so they caress each others’ soul ears, their cheeks are blushing, and they get excited. And when the two notice each other’s hot cheeks they let their lips meet and their bodies get close.

In the sequence that goes from caressing to fucking it should be noted that the difference between the two is so thin that they are almost indistinguishable. Although the inner thoughts of the two fill the frames as narration, it is impossible to determine if it is Terumi or Rōta who utters things like “I want to touch” and “I want to be touched”. Even if the reader identifies with the story’s narrator Terumi, he can no longer tell who Terumi is.

This is an intentional manipulation by the author. As the story progresses from caressing to kissing, the two boys are drawn almost as mirror images, stressing the equal gender, but it could maybe also be read as a message about love having neither a lord nor a customer. “Tamamimi” features ideal love of the kind “you and I become one”.

Dream Users/夢使い

The ero-manga “Dream Users”/夢使い (Kodansha/構談社, 2002) by Ueshiba Riichi/植芝理一 shows no mercy. Cross-dressing boys lure girls to another world, where their alter egos grow penises and transform themselves into boys who rub their penises against each other. Although the manga can be seen as following the schema of “yaoi/BL”, the main focus is on “mating with myself”. As the otherness is extinguished, the unity causes a gravitational collapse towards the vanishing point of autoeroticism. We end up in the “cute me” universe with no outside world.

Boy gang rapes

Departing from “Tamamimi” (with its one-on-one coupling) and “Dream Users” (myself-on-myself), Nagayama next illustrates how individual humans don’t matter when the purpose is autoeroticism.

In the popular gang rapes of “many on one” (多数╳一人), the more “seme” that are participating, the more their individuality disappears, and the reader’s consciousness is focused on the raped boy, the “uke”. The raper squad thus turns into “a role that appeared for the sole purpose of raping cute me”.

This is the ecstacy that is at the heart of “Spitfire”/スピットファイア (Moeru Publishing, 2005) and similar stories. No matter how they are set up with boy gangs and raped boys and so on, both the “uke” and the “seme” will eventuall become “me”.

Autoeroticism and porn

Nagayama ends his analysis of the autoerotic aspect of shota by saying that it is of course only one way in which one can make sense of shota. But he argues that the position of shota is productive when trying to deconstruct ero-manga as a whole by using this keyword, and not only ero-manga for that matter, but porn in general.

Comment