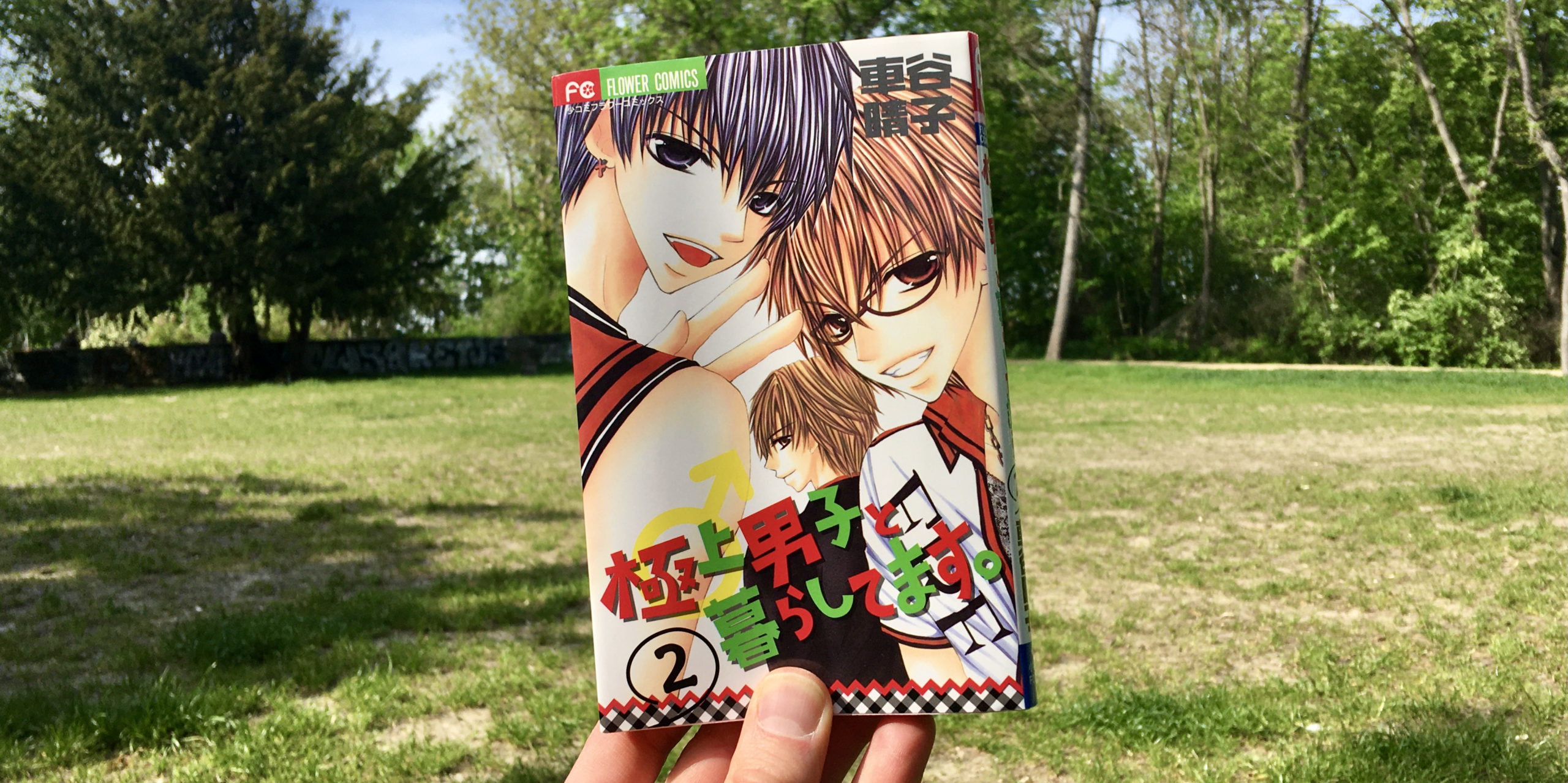

Springtime is for going to a park with a shōjo manga, but I’m almost having enough of Ruki, the protagonist of Kurumatani Haruko-sensei’s Gokujō danshi to kurashitemasu 2 (Shōgakukan 2007) – this time very freely translated by myself as Help, I can’t resist the super sexy boys I’m forced to live with! She’s such a crybaby, Ruki, always insecure about whether Senri-kun loves her or not. I mean, we can all relate, but the shōjo genre indulges in this theme like a sugary cake. It’s lovely. At times. And after a while you’ve had enough.

Even so, reading the second part of this two-tankōbon series is so enjoyable and interesting. A couple of observations:

Honour galore

Whenever people criticise “cultures of honour” for protecting the purity of their women, the assumption is that their own enlightened culture has done away with such misogynistic traits. But honour is a facet of all cultures. It always bubbles underneath, but is only noted when it comes out in a particularly brutal way. A functionalist would probably say that the function of honour is to make relationships work in a way that is productive for society.

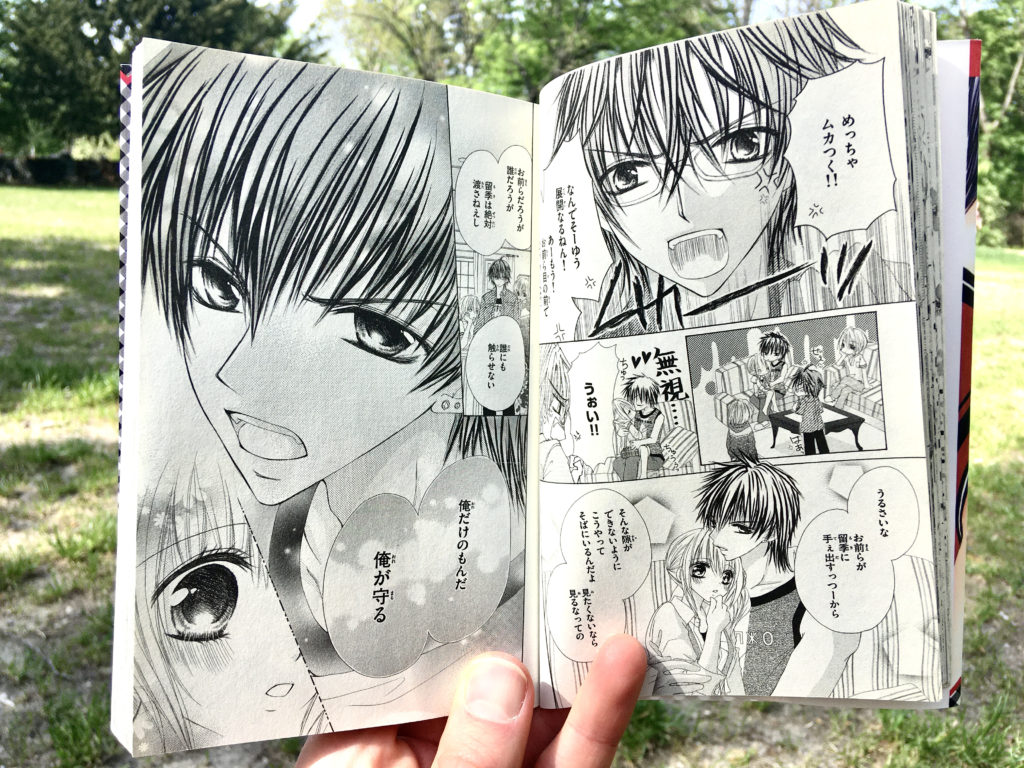

Shōjo manga revels in honour, and shows how girls and boys alike use it to manifest their love. Gokujō danshi to kurashitemasu 2 provides a beautiful example of this. The whole setup is a “reverse harem” in which 16-year-old Ruki is constantly courted by super sexy boys, to the despair of her boyfriend Senri-kun, whose sole task it seems to be to protect Ruki from the horny boys lest she succumbs to their moe-ness. Since they are all living together, this means Senri-kun must keep an eye on Ruki at all times. But as soon as he’s out of the room – he has to go to the bathroom after all – the boys are at it, and Senri-kun comes back only to see his Ruki violated. And this is what he expresses in rage at such an occasion:

I’ll make sure that you won’t get the slightest opportunity to touch Ruki. … I won’t hand over Ruki to you or anyone else. I won’t let anyone touch her. She’s only my thing and I will protect it!

Gokujō danshi to kurashitemasu 2, p. 38-39.

Okay, I took some liberties when translating the last line. It should of course be “She’s only mine and I will protect her”. The Japanese mon is used as an intensifier, but it is derived from mono, meaning thing, and the objectification of Ruki adds to the honour concept: She is owned by him, and a man’s honour is slighted if another man encroaches on his property. While this kind of objectification of women is sometimes criticised, it is also the driving force of shōjo manga, and Senri-kun’s passionate speech about protecting his property results in Ruki expressing “Oh Senri-kun, I love you!” on the next page. Owning someone feels good, but so does being owned! Shōjo manga sums up the dynamics of heterosexual love so blatantly that it can’t be ignored.

But the owning goes two ways. A couple of chapters later it’s time for the culture festival at the school. Ruki and Senri-kun are in the same class, and the class decides that their contribution to the festival will be a cosplay host club, where the class’s sexy boys dress up as waitors and serve female customers. This seems to be a real facet of Japanese school life, as maid cafés often feature at school festivals in animes – talk about being schooled into roles in society! And talk about having an established framework for the appreciation of young boy beauty. In any case, Ruki is devastated that other women will touch Senri-kun. She protests against the host club idea until she realises that the cosplay aspect means she will be able to see Senri-kun in some kind of sexy outfit. But of course, as soon as she sees him serving (and courting) female customers, she turns again and becomes the crybaby that I’m starting to get sick of.

A manga in a manga

The next chapter begins with Ruki coming crying to Senri-kun in their house. He asks what’s bothering her, and she explains:

In this month’s issue of Sho-comi, Shun-sama and Ai-chan separated!

Gokujō danshi to kurashitemasu 2, p. 127.

Shun-sama is the fictional boy that Ruki was in love with and mixed up with Senri-kun when they first met. A footnote explains that Ai-chan is Shun-sama’s partner (aite-yaku), so I guess it’s a Boys Love manga. This is but another example of how fictional and actual realities interact – within the same work of fiction! It’s like a Russian matryoshka doll: The reader of this manga is reading about a reader of another manga. It seems to me that there is much thinking about fictional and actual realities in Japanese popular culture, and that young people are fostered into this discussion through its steady emergence on the pages of shōjo and probably other manga.

What do you think? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments or in our shota forum!